We are surrounded by objects that seem very ordinary, but once we look closer, they often reveal deep connections to the history of our state and our communities. In this Object History, Pao Vue writes about the threadbare baby sash he found in his mother’s room. It turns out, this sash once saved his life and helps tell the history of the Hmong community in Wisconsin.

We are surrounded by objects that seem very ordinary, but once we look closer, they often reveal deep connections to the history of our state and our communities. In this Object History, Pao Vue writes about the threadbare baby sash he found in his mother’s room. It turns out, this sash once saved his life and helps tell the history of the Hmong community in Wisconsin.

The Pao Vue (Xeempov Vwj) Family’s Baby Sash

A Hmong baby sash (daim nyias) consists of two components, a wrap (nyias) and a tie (hlab). The wraps are usually embroidered with hand-stitched designs while the ties usually consist of a large sheet of cloth folded into a long rope-like object. The tie is then attached to the wrap using an overlaying sewing technique known as ‘holding under/beneath the needle (tuav qab koob)’ to maximize durability. The sash is usually well-maintained and kept in good condition in order to show-off the intricate embroidery while carrying around the infant child. Intricate and carefully maintained baby sashes are a sign of prestige in Hmong culture. Once the sash becomes so worn that passersby would notice, it either gets repaired or replaced with a new one.

How the sash was made

What makes this baby sash fascinating is not just that it was a baby sash, but rather, that is it a worn and threadbare baby sash. To me, it is the story behind its current condition that makes this baby sash truly special.

This worn and tattered tie is what remains from a once beautiful sash made from hemp fabric and interwoven with some of the most expensive colored threads available in the highlands of Laos in 1979. It was meticulously hand-stitched by a Hmong woman named Madam Phoua La Chang (Niam Npuag Laj Tsab) using a sewing technique known as ‘braided thread (xov sib qhaib).’ This baby sash was more valuable than many others not just because of the expensive materials used, but also because the tie was hand-stitched with the same expensive materials and covered with beautiful embroidery designs to match the original wrap. It was quite common for a woman to spend hundreds of labor-hours over a period of six months or more to complete a hemp sash of such quality.

Madam Phoua La was able to obtain expensive materials to weave this sash because up until 1979 her husband was a high status, well-respected, leader of their village. In fact, the village was named after her husband, Phoua La, and was known as Phoua La Village.

The sash was beautiful, but this is more than a story about a beautiful well-maintained sash. This is a story about how the sash came to be tattered and worn-out.

What happened next

Madam Phoua La created this beautiful sash in 1979. Unfortunately, the mid- to late 1970s and early 1980s were times of turmoil, instability, and uncertainty for many of Laos’ citizens. The communist organization and political movement, the Pathet Lao, had emerged victorious from the Vietnam War and had implemented a genocidal agenda to purge the country of those who had sided with the United States. It was not long after Madam Phoua La finished this baby sash in late May of 1979 that warnings of the encroaching purge reached Phoua La Village. Many villagers, including Madam Phoua La, responded to the warnings by making plans to flee the area. Madam Phoua La was not able to carry the newly-finished sash, and had planned to bury it in a secret place with other valuables so she could one day come back for it.

My family came from another village in Laos, and was also fleeing the communists.

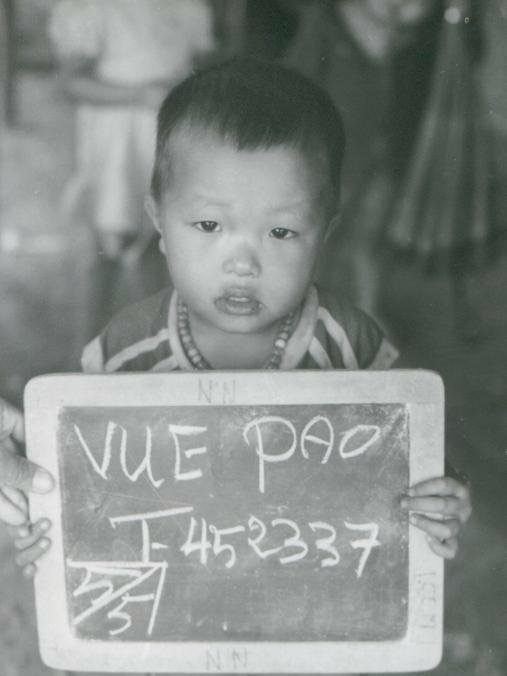

Just as Madam Phoua La was preparing to bury this baby sash, my mother, Yer Yang (Ntxawm Yaj) who was seven-months pregnant with me, passed through Phoua La Village. My mother saw the sash and asked about buying it. Madam Phoua La thought it over and elected to sell it to my mother for a generous price of 3,000 Lao kip (a very large sum of money at the time) both as an act of friendship and because Madam Phoua La knew deep within her (and confided to my mother) that she will likely never return. This was how the sash came to my family’s possession.

The sash spent the next couple years holstering myself to my mother’s chest as she and my family hid in the jungles of Laos. Because the sash held me to my mother’s back, my mother could keep her arms free while my family was escaping.

We eventually ran, walked, and crawled our way to Thailand in 1981. The unforgiving conditions of fleeing the communists wore out the baby sash that Madam Phoua La made to the point where it became unusable. When this happened, my mother replaced the hemp wrap with a new cotton wrap that she purchased while living in the Ban Vinai refugee camp in Thailand.

Coming to Wisconsin

In the summer of 1982, my family and the sash came to the United States and settled in Salt Lake City, Utah. My family continued to use the sash until the wrap had worn down beyond use and was discarded in 1984. However, my mother elected to keep the tie as a reminder of the horror that she, my family, and many other Hmong families went through.

That same year, my family moved to La Crosse, Wisconsin to be closer to our extended families and relatives who, along with other Hmong, have already established a small but growing Hmong community in the area. Wisconsin (along with Minnesota and California) was an ideal state to settle for many of the first Hmong refugees because it had some of the better government assistance programs in the nation. In addition, Wisconsin also had many knowledgeable and dedicated non-profits and church organizations that helped Hmong refugees acquire the necessary skills to find jobs to provide for their families.

My mother did not speak of the baby sash, but kept it hidden in a clothes drawer for many years. I found it one day while going through the house and asked my mother what it was and why she kept such an old and ‘worthless’ piece of cloth around. It was then that I learned that this ‘worthless’ piece of cloth had saved my life multiple times. Other than my family, this sash perhaps played the most crucial role in my being alive, growing up in Wisconsin, and proclaiming myself a Wisconsinite.

Thus, this is more than just a story about a sash.

This baby sash tells the story of the life-or-death struggle that many Hmong families went through after the Vietnam War. For me, it is a constant reminder of what happened to many Hmong who supported the United States during the war and who were forced to flee with only what they could carry. It is a constant reminder of the horror that many endured for years while hiding in the jungle of Laos with not much more than the clothing on their back.

When I look at this sash it reminds me of the countless casualties of war; of the indomitable will of the human spirit; and of reason why many Hmong have come to call Wisconsin ‘home.’

Written by Pao Vue (Xeempov Vwj), July, 2018.

Object history written July, 2018