It is often said that necessity is the mother of invention. This holds true for the Feed Grinder.

In the late 1920s, agronomist Clair Mathews noticed that the 1,200 Guernsey cows under his watch at the Dougan Dairy Farm in Beloit, Wisconsin, were not fully digesting the grain they were eating. As a result, they were not receiving the full nutritional benefit of the food.

Mathews, who had studied agronomy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, knew that a roller mill could be used to flatten the grain, thereby making it easier for cows to digest. However, when he suggested the use of a roller mill to the owners of the Dougan farm, they realized the mill would be too expensive to purchase. In a moment of rural ingenuity inspired by a mortar and pestle Mathews saw at a Beloit drugstore, he decided to make his own mill.

Using spare parts from the nearby Walsh Cabbage Farm, Mathews set to work to recreate the grinding he had witnessed with the mortar and pestle. Old wagon wheels anchored his design, which also incorporated a strainer funnel as the hopper and an old washing machine motor to generate power. When this initial motor failed to generate the power he needed, Mathews borrowed a 1.5 horsepower Fairbanks motor from the Dougan farm, added a belt needed to power the machine, and set to work processing some corn meal. The meal was ground under pressure and partially cooked in the process.

When the meal landed in the tray at the bottom of the machine, it emerged as a puffed product. By accident, Mathews’ Feed Grinder produced the precursor to a whole new type of snack food: the Korn Kurl.

Excited about the prospects of his initial design for a feed grinder, Clair Mathews approached his friend Clarence Schwebke, a machinist in South Beloit, to manufacture a commercial version of the machine.

Upon completion, they immediately put their new model to good use. Because the Great Depression was in full swing by this point, many people were keeping rabbits, which were easy to care for and a good source of food. Mathews used his new machine to produce Alpha Flakes, from alfalfa, for rabbit feed.

The Flakall Corporation, Beloit

Looking to expand their production, and to drum up some more money, Mathews sought investors who might be interested in his new feed grinder. He tried to interest both Quaker Oats and Henry Ford. Mathews traveled to the 1934 Chicago World’s Fair, where Ford had an oil-extracting machine on display. Upon arrival, he saw an Allis Chalmers roller mill and knew that this was his opportunity to impress Ford with his own invention. His plan worked, as Ford invited Mathews to Detroit to work in his laboratories, and eventually put the machine on display at the fair. Although Mathews’ machine ended up being too inefficient at soy oil extraction for Ford’s purposes, his interest in Mathews nevertheless gave a boost to the invention.

Back in Beloit, Mathews continued his quest to expand. He and Schwebke approached Harry Adams, a local lawyer and former Beloit mayor, to get him interested in the machine and its potential. Adams, reportedly the first customer to receive regular milk deliveries from the Dougan Dairy Farm when they started a route to the city, was intrigued. They enlisted Earl Baker, an engineer from Beloit Iron Works to refine the invention, and together formed the Flakall Corporation in 1933. Clair Mathews became the corporation’s first president, while Clarence Schwebke served as the secretary and treasurer, Harry Adams the corporation’s Wisconsin agent, and his son, Allan Adams, the first salesman.

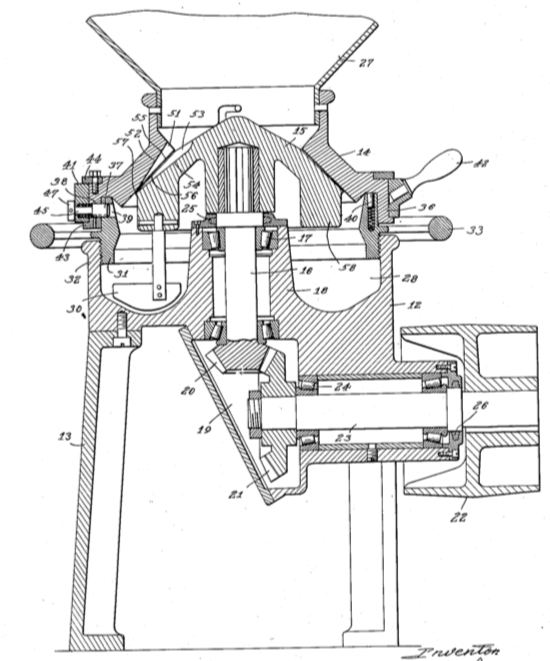

Over time, the men filed four different patents to protect their work. Clair Mathews was issued patent 1,987,941 in January 1935 for his “Feed Grinder” machine. The Flakall Corporation was issued patent 2,120,138 in June 1938 for their “Method of Producing Food Products.” Finally, Clarence Schwebke and Frank E. Hoadley were issued patent 2,295,868 in September 1942 for their “Process for Preparing Food Products,” and patent 2,350,643 for a “Machine for Preparing Food Products.”

Written by Cheryl Kaufenberg, September 2019.