The Hodag and Paul Bunyan folklore are two of the most iconic stories of the American frontier. The Hodag is a mythical creature from the Northwoods that is described as a dragon-like creature with horns, sharp claws, and a spiked tail. Paul Bunyan is a legendary lumberjack who is said to have created the Great Lakes, the Grand Canyon, and the Mississippi River. Both stories are rooted in American folklore and explain a transitional time in Wisconsin’s history from logging to other industries.

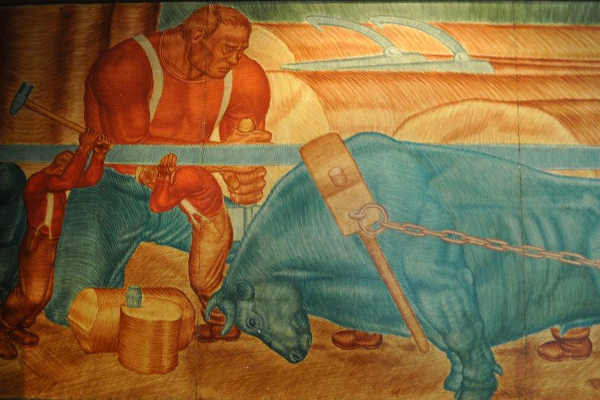

According to the lore, Paul Bunyan was born in the Northwoods to giant parents. Paul traveled westward with his loyal companion, Babe the Blue Ox and left his mark on the land by creating lakes and mountains with his footsteps. Most notably, Paul is known for his logging adventures and clearing vast forests to make way for settlements. The first written stories about Paul Bunyan appeared in 1910 in a book titled “Tales of Giant Folk” by William B. Laughead, which is a collection of folk tales about giant-like characters from around the world. Oral stories about Paul Bunyan had been circulating for decades prior to the book’s publication. The first known reference of Paul Bunyan emerged in the March 17, 1893 issue of Gladwin County Record in Michigan. Much like the preservation of the Hodag myth, life lessons from Paul Bunyan continue to be embraced through physical representations like the Paul Bunyan room at the Memorial Union at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The 40-piece mural set, painted by James Watrous from 1933 to 1936, symbolizes colonial vitality and strength.

However, the Hodag was not widely associated with Paul Bunyan in literature until 1929, when Eugene Shepard, the creator of the Hodag myth, published Paul Bunyan: His Camp and Wife with his wife Karretta Gunderson Shepard. The book is illustrated with Shepard’s original drawings of Paul Bunyan and the Hodag and became the source material for other authors of well-known Bunyan books. Though this 1929 publication became the most influential connection between the two figures, sources note that the Hodag had long been included in Paul Bunyan stories, and printed evidence dates back as early as 1910.

The Hodag myth and Paul Bunyan have a unique relationship. The Hodag is often observed as a symbol of nature’s power, and Paul Bunyan represents man’s power over nature. While the Hodag is seen as a wild and dangerous creature, Paul Bunyan is seen as a hero for his ability to tame the wilderness with his strength and courage. The stories explain how people came to terms with the harsh realities of life on the frontier. Paul Bunyan, a mythical lumberjack in northern America, represents the civilized aspect of frontier life while the Hodag embodies the savage and paranormal world of America’s untamed wilderness. Both myths exist as two sides of the same coin to describe Wisconsin’s living conditions and cultural attitudes during the pioneer days, as well as mythologize Wisconsin’s past.

Written by Sophie Mullen, May 2023.

Sources

Charles E. Brown, Paul Bunyan Natural History: Describing the Wild Animals, Birds, Reptiles and Fish of the Big Woods about Paul Bunyan’s Old Time Logging Camps. Madison: Self-Published, 1935.

Michael Edmonds, Out of the Northwoods: The Many Lives of Paul Bunyan. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2009.

Lake Shore Kearney, The Hodag and Other Tales of the Logging Camps. Wausau, and Madison, Wisconsin: Democrat Printing Co., 1928.

Craig William Kinnear, The Legend of Logging: Timber Industry Culture and the Rise of Paul Bunyan, 1870-1945. PhD Diss., Notre Dame University. June 2016.

University of Wisconsin – Madison. “James Watrous – Paul Bunyan Murals.” Public Art at UW-Madison. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://publicart.wisc.edu/james-watrous-paul-bunyon/.

Colin Woodard, “How The Myth of the American Frontier Got Its Start,” Smithsonian Institution, 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-myth-american-frontier-got-start-180981310/.