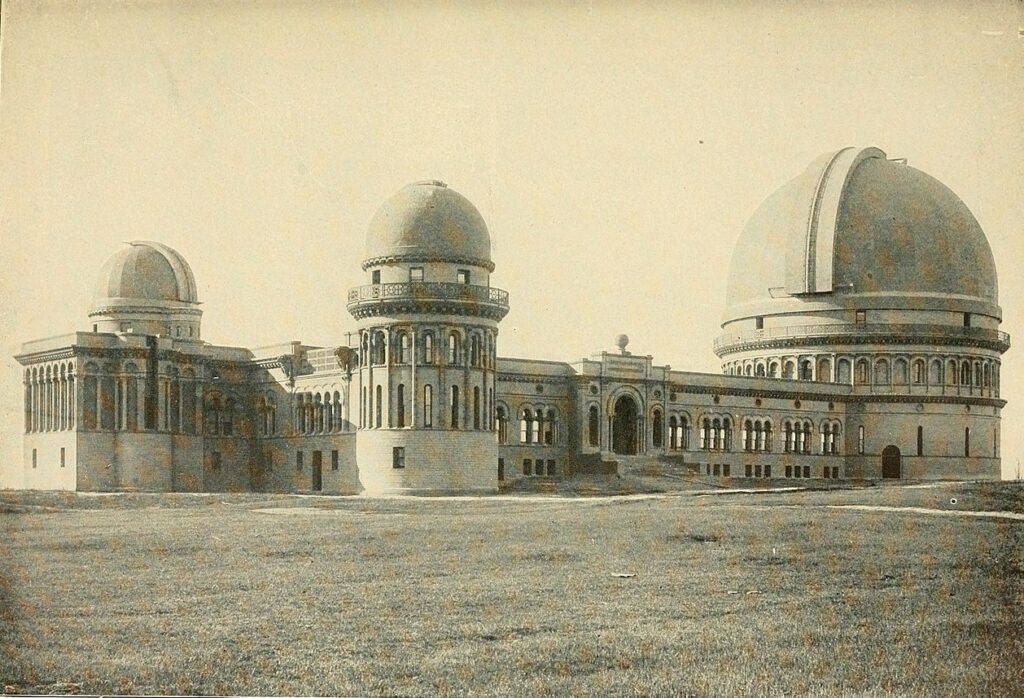

In the 1800s, astronomers valued telescope magnification to investigate planets and stars. In the 1900s, astronomers started to ask questions about the structure of our galaxy, the Milky Way, which lead to greater emphasis on light-gathering power. By 1951, William Morgan at the Williams Bay, Wisconsin, Yerkes Observatory concluded that the Milky Way existed in a spiral structure. Also, the study of astrophysics began in the early 1900s as astronomers saw the connection between physics and astronomy. Yerkes Observatory is known as a “birthplace of modern astrophysics” because the observatory was the first that focused on research and had a telescope with both spectroscopic and photographic capabilities.

Spectroscopy is the study of light dispersion to investigate an object’s characteristics. In astronomy, spectroscopy was novel because the procedure could estimate the distances between stars and the size of stars. In 1926, Otto Struve, an astronomer at Yerkes Observatory, used spectroscopy to discover that interstellar gas existed uniformly in the Milky Way.

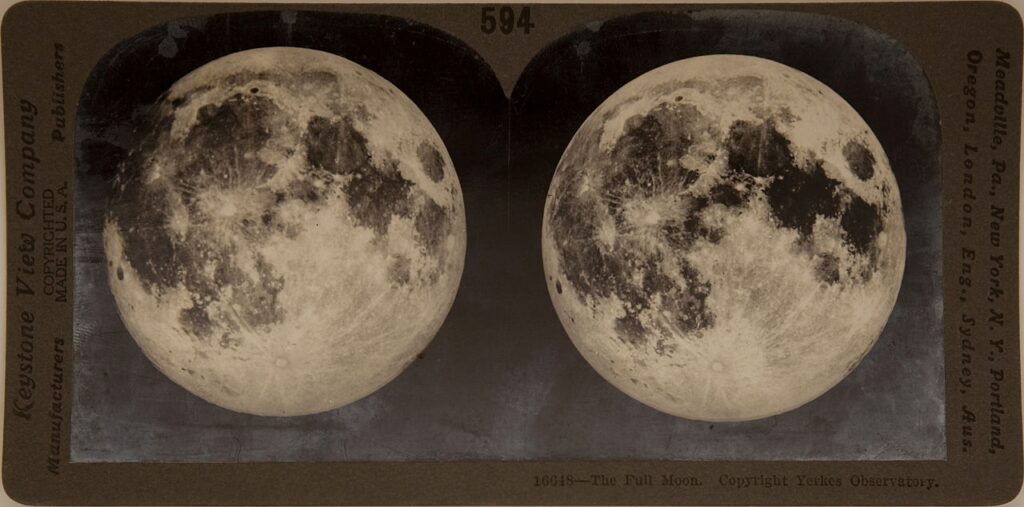

Along with spectroscopy, photography helped advance astronomy research in the 1900s. Photography was important because pictures could see observations through the telescope that the eye could not. However, the most effective light range for photography is different than the best light range for the human eye. The 40-inch refracting telescope at Yerkes Observatory was one of the first telescopes that was optically designed for photography over human vision to create higher quality pictures.

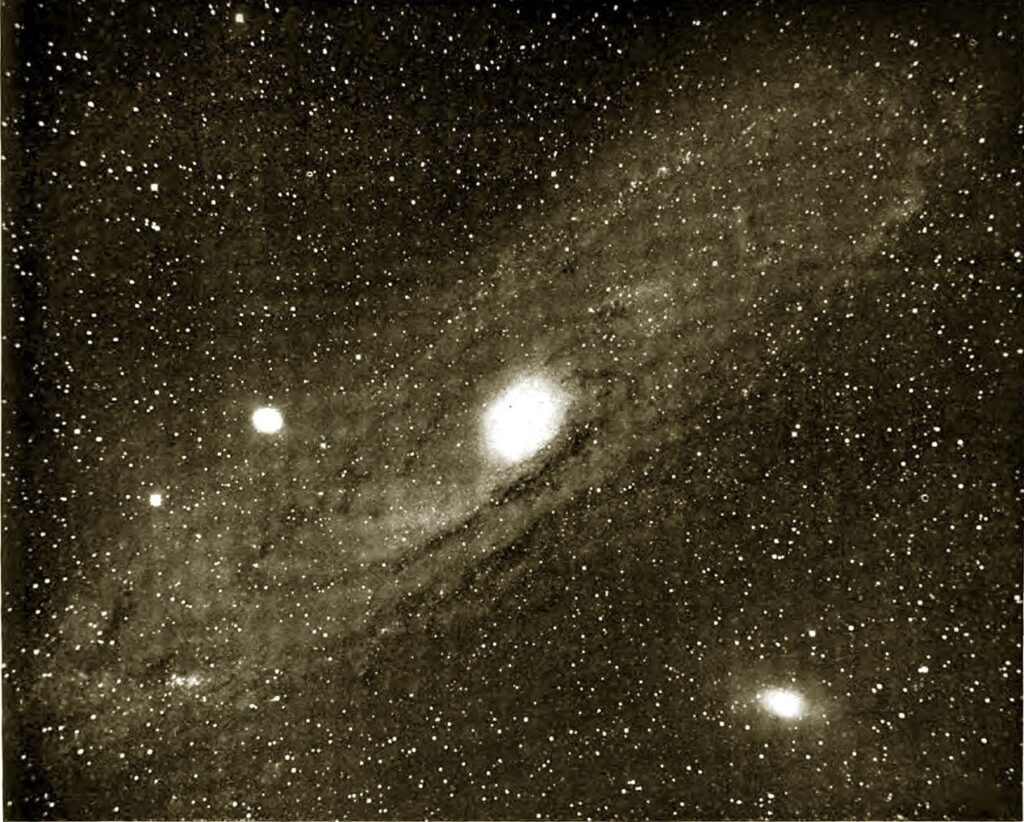

The biggest astronomical discoveries from the 1900s revolve around the work of Edwin Hubble, who did his graduate work at Yerkes Observatory. In 1929, Hubble’s Law was published stating that the universe is expanding. Hubble’s work gave evidence for the Big Bang theory of the universe. The Big Bang model affirms that the universe was created at one instance that was followed by an initial expansion. The theory suggests that ever since, the universe has been constantly cooling and, as a result, expanding.

Yerkes Observatory also made many contributions to astronomy during the 20th century. The 40-inch refracting telescope discovered the atomic explosion of the star named T-Corona Borealis. Additionally, over 100 years, the 40-inch refractor took pictures of globular star clusters, which helped with the study of star motion. Other telescopes at the observatory helped discover the presence of carbon dioxide on Mars, several moons on Uranus and Neptune, and the behavior of white dwarf stars.

Written by Kelsey Corrigan, December 2014.

SOURCES

“Atomic Explosion of Star Discovered by Observatory,” The Waukesha Freeman. January 9, 1946.

Richard Berendzen, Man Discovers the Galaxies. New York: Columbia University Press, 1984.

Bruce Bond, “A Celebration of Light: Yerkes in Perspective,” Astronomy Magazine, December 1982.

Rose Cour, “Observatory at Lake Geneva a Popular Spot,” The Chicago Tribune, 31 August 1938.

Michael Ference, “The Graphic Laboratory of Popular Science,” The Chicago Tribune, 31 October 1943.

George Hale, National Academies and the Progress of Research. Lancaster: New Era Printing Company, 1915.

James Lattis. Personal Interview. 4 November 2014.

Peter Susalla and James Lattis, Wisconsin at the Frontiers of Astronomy. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Astronomy, 2009.

Donald Osterbrock, Pauper & Prince: Ritchey, Hale, & Big American Telescopes. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1993.

Donald Osterbrock, Yerkes Observatory, 1892-1950. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

“Two Kinds of Telescopes,” Astronomy GCSE. http://www.astronomygcse.co.uk.

Deborah Warner, Alvan Clark & Sons Artists in Optics. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1968.

“What the Yerkes Telescope Promises to Science,” The Chicago Tribune. 12 September 1897.

Helen Wright, The Legacy of George Ellery Hale. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1972.

“Yerkes Observatory Repairs,” The Chicago Tribune, 2 September 1897.