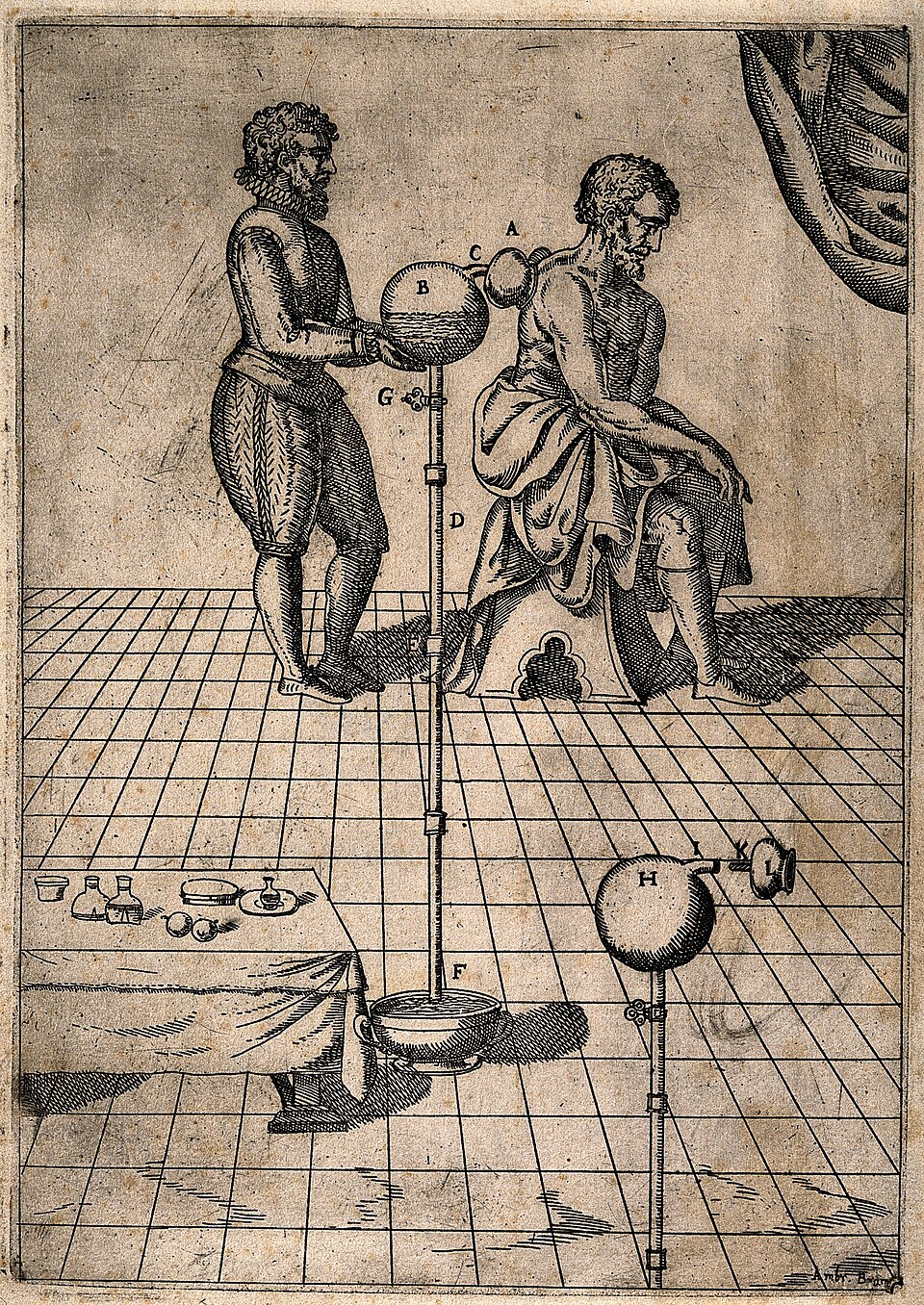

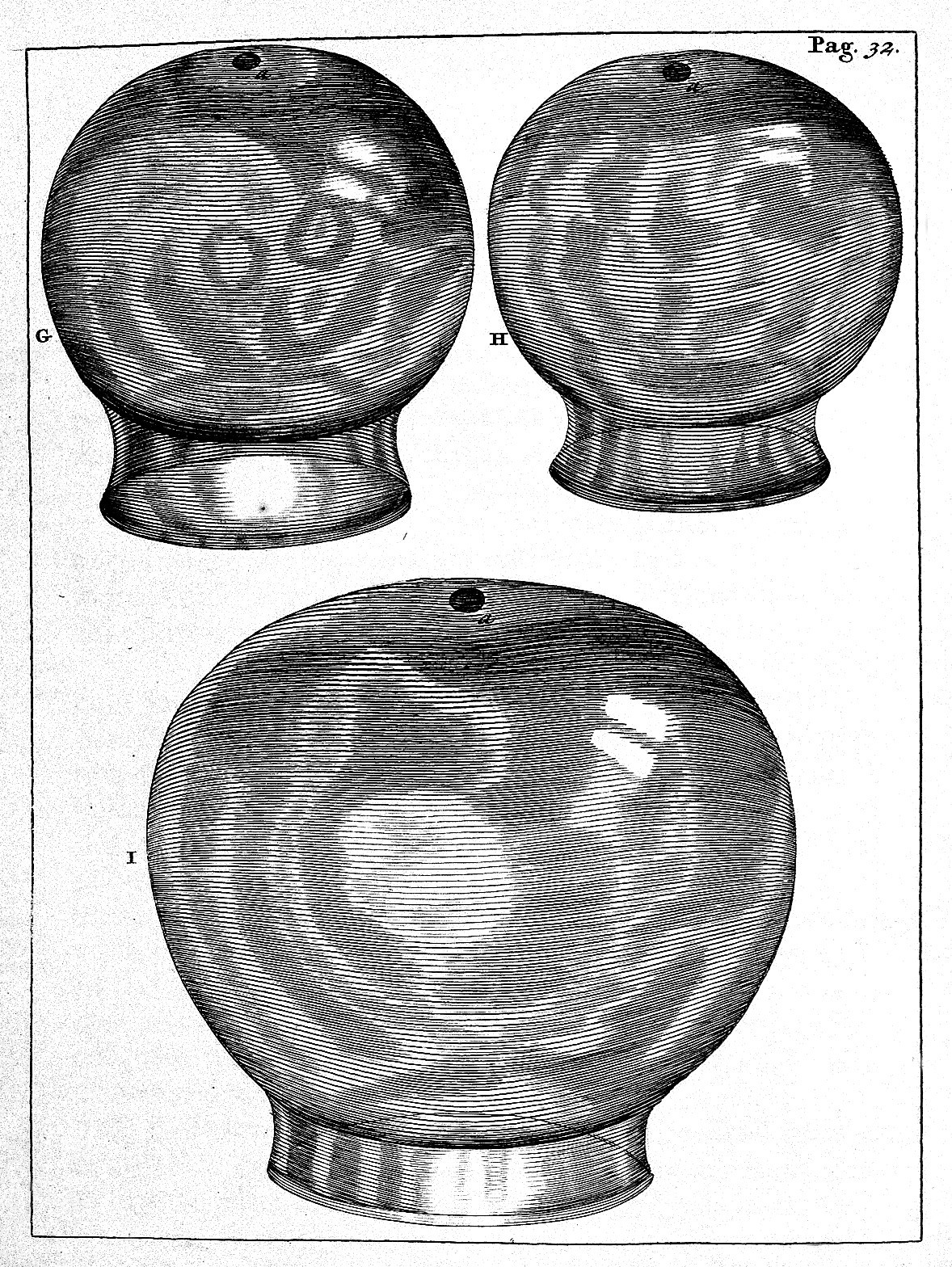

Until the late nineteenth century, cupping was widely used for the treatment of inflammation and deep-seated pain believed to be due to an imbalance of the humors. A physician or barber surgeon would begin cupping by selecting the appropriate cup based on the amount of blood to be removed or the size of blister to raise. 1 The surgeon would then place the cup over the affected site and remove the air to create a vacuum. Lighting a flame under the glass or using a syringe to eliminate the air could create the vacuum. The cup would be left on the skin long enough for a blister to develop, the glass would then be removed and, in wet cupping, a scarificator would be applied. The scarificator is a square device that would release small lancets to break the skin, the glass would be reapplied and a vacuum created so that the blood could be collected. In dry cupping the blister would be left raised. 2

Example Case

During the Wisconsin State Medical Society meeting in 1875 Dr. Ira Manley of Markesan, WI presented a case in which a “strong young man” complains of pains in his stomach after bringing in the harvest. After the application of 16 cups and scarification to his back, the man was reportedly cured.

Within a few decades, cupping would fall into decline as new bacteriological models of health and illness replaced humoral theory.

Written by McKenzie Bruce and Eleanor Miller.

SOURCES

CElizabeth Allen and J.L. Turk, “Bleeding and Cupping,” Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Vol. 65 (1983).

W.F. Bynum, Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. 1994.

H. Cao, M. Han, X. Li, S. Dong, Y. Shang, Q. Wang, S. Xu and J. Liu, “Clinical research evidence of cupping therapy in China: a systematic literature review,” BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Vol. 10 (2010), 1-10.

J. Haller, “The Glass Leech: Wet and Dry cupping in the 19th c.” New York State Journal of Medicine, Vol. 73 (1973), 583-592.

Monson Hills, “A Treatise on the Operation of Cupping: General Rules,” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (1833), 261-273.

Howard A. Kelly, A Cyclopedia of American Medical Biography: Comprising the Lives of Eminent Deceased Physicians and Surgeons from 1610 to 1910. Baltimore: The Norman, Remington Company, 1920.

R.L. Numbers and J.W. Levitt, Wisconsin Medicine: Historical Perspectives. University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI. 1981