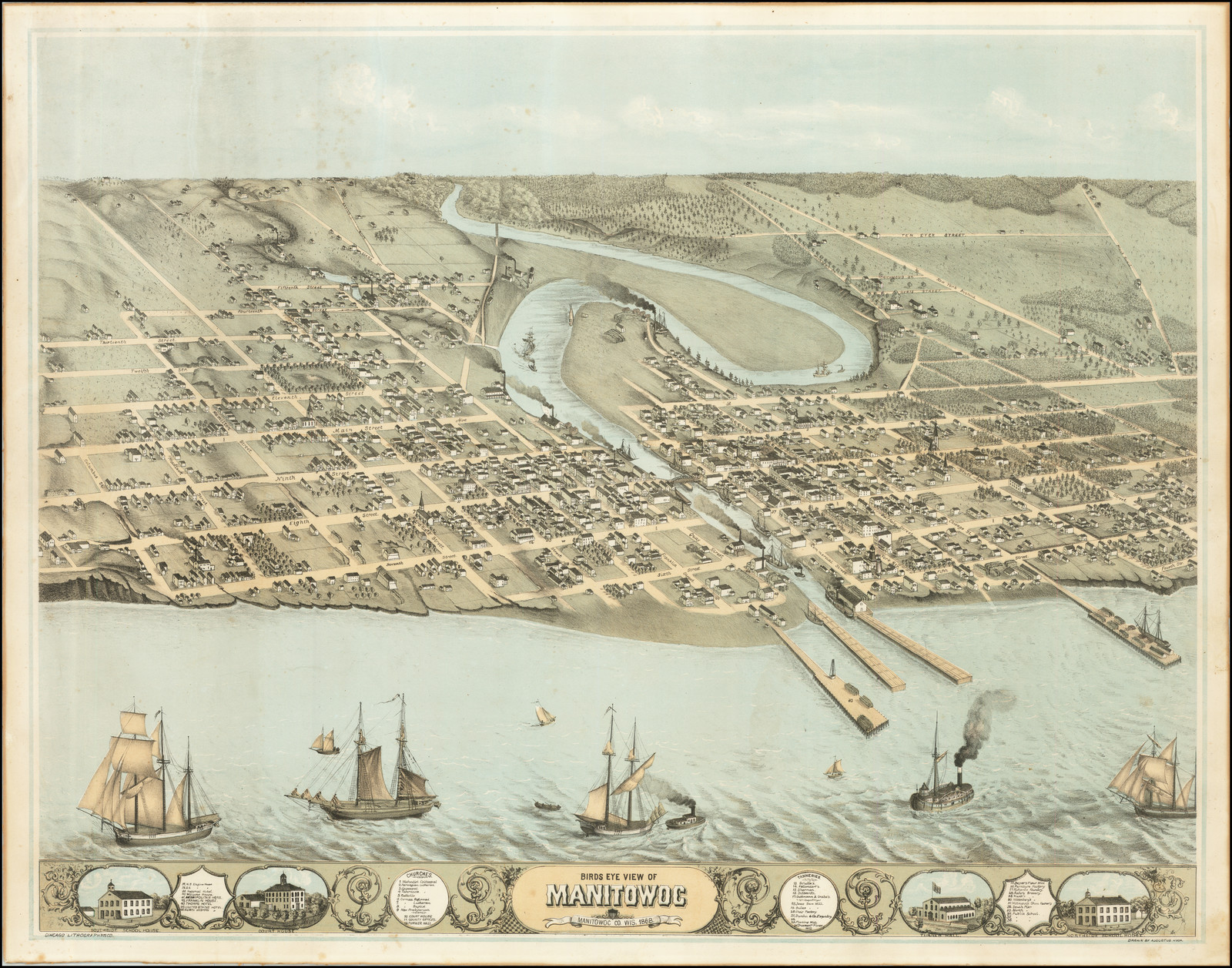

Many of us can easily picture a lighthouse in our minds. You may think of a tall structure that’s right along a lake or ocean, illuminating the water and land it protects. Whatever comes to mind, lighthouses have an everlasting cultural presence far beyond their functionality. Lighthouses have long been known for their role in navigational assistance and as a beacon for maritime activity. Even as lighthouses continue to face a decline in necessity due to improving navigational technologies and GPS, their structures remain crucial to many coastal town identities. The Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, which sits quaintly on Lake Michigan, is no exception.

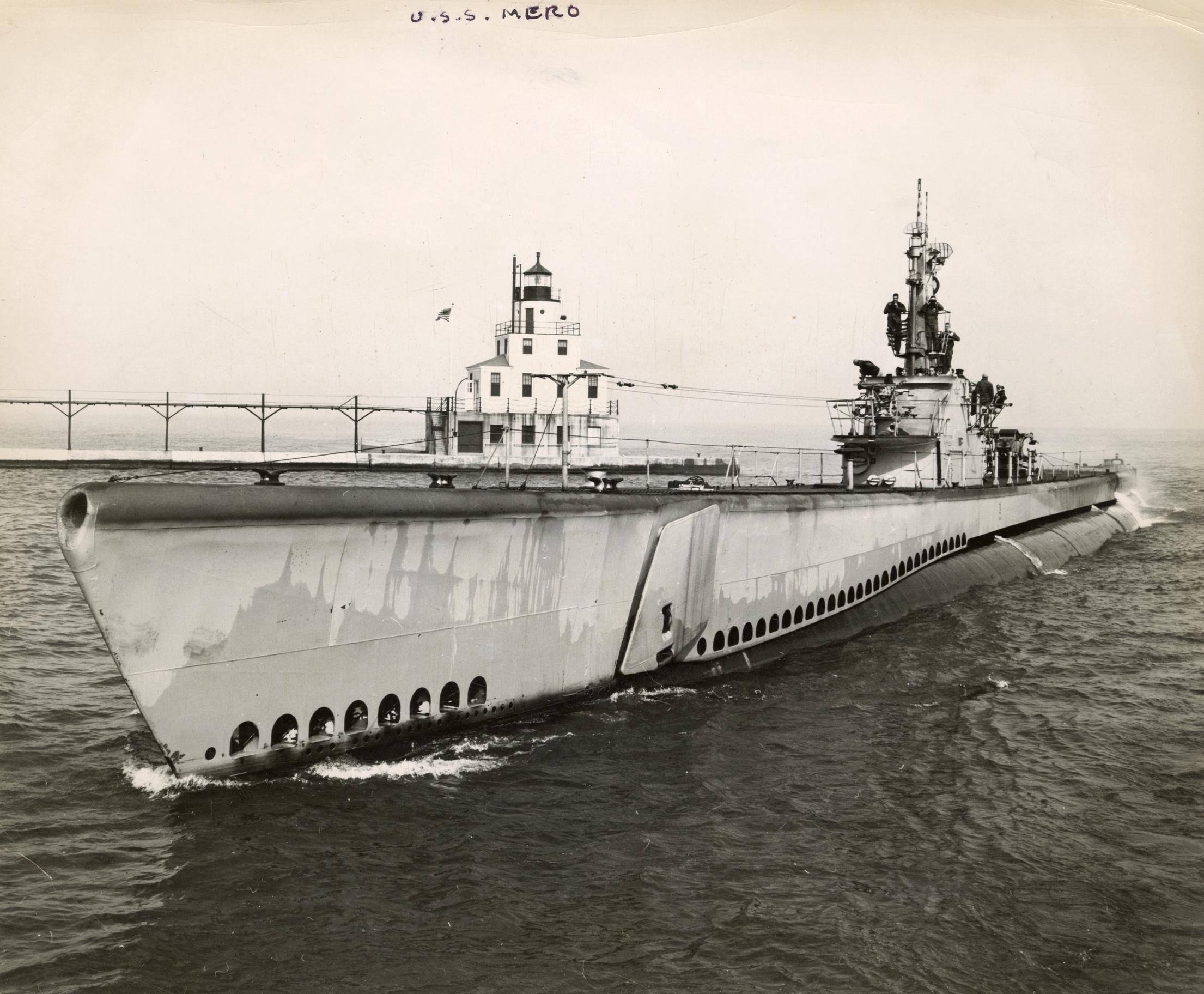

Manitowoc has always exuded an aura of maritime grandeur from its participation in shipbuilding in the late 19th century to its submarine construction during WWII. Shortly after its establishment in 1836, the town recognized it had a suitable harbor which could facilitate nautical travel and trade. Soon the need for a navigational aid arose in this bustling harbor town, and the first light tower was built in 1840 by the city of Manitowoc, establishing lighthouses as an important guide for the ships entering the city. As Manitowoc’s shipping industry grew, the city was able to invest in new constructions of light towers, ultimately resulting in the installation of the Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse in 1918 to replace the previous tower.

The Manitowoc Breakwater Light stands at 52 ft on a concrete pier with a steel frame. It is painted white and installed with a fourth order Fresnel lens. The Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse had a multi-purpose design. Its basement served as a boathouse, the first story functioned as a power room with hollow tile lining, and the second story was equipped with a shower, lavatory, and furnished with desk and chairs. Joseph Napiezinski held the position of lighthouse keeper from 1911 to 1941, and Ross F. Wright was his first assistant from 1911 to 1932. In addition to their responsibilities of operating the light and fog signal, the keepers remained vigilant for anyone in need of assistance on the water. Throughout its more than 80 years of operation, the Breakwater Lighthouse has served as a guiding light for those coming in and out of Wisconsin. In 1971, the lighthouse was automated so that it could operate without the need for a keeper. Still sitting at the end of Manitowoc’s harbor, visitors and locals can walk along the north pier to visit the lighthouse and appreciate the city’s maritime history. Tourists and residents can also visit the Wisconsin Maritime Museum, which sits not too far from the Breakwater.

In 2009, a New York businessman named Philip Carlucci bought the lighthouse after it was determined to be excess by the U.S. Coast Guard. Carlucci had dreamt of owning a lighthouse since he was a kid, and when he came into possession of the Breakwater, he decided to restore it. By the Lighthouse’s 100th anniversary in 2018, Carlucci repainted the structure and renovated the lighthouse to its previous historical layout. It has since continued to be a place where visitors can come to appreciate the beauty of the lighthouse as well as the scenic view of Lake Michigan. As navigational technology advanced and Manitowoc’s industry evolved over time, the lighthouse continued to adapt and is a testament to the perseverance of lighthouses as an entity.

All throughout the Great Lakes and the country, lighthouses are often visited and appreciated for their design, even with so many of them being obsolete. The Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse is not only cherished by its charm but also for its lasting testament to the everlasting maritime industry in Manitowoc.

Written by Bella Roberts, May 2023.

SOURCES

Kraig Anderson, “Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse.” LighthouseFriends (website). Accessed May 9, 2023. https://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=250.

Bryan Penberthy, “Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse.” US Lighthouses (website). Accessed May 9, 2023. https://www.us-lighthouses.com/manitowoc-breakwater-lighthouse.

Bruce Roberts, Western Great Lakes Lighthouses: Michigan and Superior. (Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot Press, 2001.)

United States Coast Guard, “Manitowoc North Breakwater Lighthouse.” Accessed May 9, 2023. https://www.history.uscg.mil/Browse-by-Topic/Assets/Land/All/Article/1962156/manitowoc-north-breakwater-lighthouse/.

Ken Wardius and Barb Wardius, Wisconsin Lighthouses: A Photographic & Historical Guide. Revised Edition. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2013.

Larry Wright and Patricia Wright, Great Lakes Lighthouses Encyclopedia. Erin, Ont.: Boston Mills Press, 2011.

This object has been featured on WPR's Wisconsin Life!

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Molly Hunken

On the western coast of Lake Michigan sits the city of Manitowoc, Wisconsin, a place known for its deep connection with the water. And along its shore, a lighthouse essential to the area’s maritime history stands tall, watching over the city. Molly Hunken climbs inside to take us on a tour of the Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum:

On the western coast of Lake Michigan sits the city of Manitowoc, a place known for its deep connection with the water and along its shore, a lighthouse essential to the area’s maritime history stands tall watching over the city. Molly Hunken climbed inside to take us on a tour.

Paul Roekle:

Okay, well, welcome to Manitowoc North Breakwater Lighthouse. You’re about half a mile out in the lake here. Ludington is about 60 miles across the lake straight over here, so you’re out in the center of things here.

Molly Hunken:

Paul Roekle is a member of Manitowoc Sunrise Rotary, a locally based group which organizes fundraising events for the community. Within the past decade, they have also become the official caretakers of the Manitowoc North Breakwater Lighthouse. The lighthouse was built in 1918 making it over 100 years old. Its name comes from the structure that it’s built on.

Paul Roekle:

When you walk out here on the concrete, that’s the breakwater. And basically what that is, it separates the lake from the harbor, and it makes a safe place for the ships to come in and be protected.

Molly Hunken:

The building itself has five stories. Its first floor is a basement which used to act as storage and a boathouse. In this portion of the basement was a dory, a small boat which lighthouse keepers used for rescues.

Paul Roekle:

But you can read stories on it where the lighthouse keepers in its day would take care of the rescues on the lake when they occurred, and even the middle of winter in a tremendous blizzard, at night, no lights, they had to listen to the sounds and actually push the boat out, hop in it, and go out and rescue people, then bring it back in.

Molly Hunken:

On the second floor, the motor room housed the motor to generate power for the light on top. Above that, sits the watch room, where lighthouse keepers used radio equipment to keep in touch with boats out on the lake. In cases of stormy weather, sometimes lighthouse keepers stayed overnight in cots in this room, though they normally slept on shore. The diaphone room on the fourth floor used to be the location of the foghorn, also called a diaphone. Ships could activate the diaphone from the lake to warn of their arrival on shore. From the deck outside, you can see the Badger Car Ferry, which has been running since the 1950s beginning its round trip between Manitowoc and Ludington, Michigan.

Paul Roekle.

That two signals. That’s a salute to us. Thank you.

Molly Hunken:

After a brief climb up a small metal ladder, you reach what most people would think of when imagining a lighthouse, the lens house.

Paul Roekle:

That’s where the light that signals to the ships is located, and this particular light could be seen from 17 miles out in a lake.

Molly Hunken:

The small room on top of the lighthouse holds no more than the light itself, with enough space for a few people around it. The expansive view looks out over Lake Michigan and the city of Manitowoc, after the need for lighthouse keepers disappeared, the building became run down. It succumbed to vandalism and the wear and tear expected for a building in the middle of a lake. But in 2011 the Manitowoc North Breakwater Lighthouse was put on auction by the Coast Guard. It was purchased by a man from Long Island, New York named Philip Carlucci for $30,000.

Paul Roekle:

You buy a property from the Coast Guard, you have to bring it up the standards and maintain it. So he stuck over $325,000 into it, to get into the condition it is in today.

Molly Hunken:

The owner and Manitowoc Sunrise Rotary are collaborating with the Wisconsin Maritime Museum, also located in Manitowoc, to return historical objects and equipment to the building. Looking forward, the owner hopes to continue restoring the lighthouse to its original state.

Maureen McCollum:

Molly Hunken brought us that story on the Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse. The building itself is part of the Wisconsin 101, project which tells our state’s history through objects. Wisconsin life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin in partnership with Wisconsin Humanities. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin life@wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook and Instagram. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Wisconsin Maritime Museum

Research for this object essay and its related stories was supported by the Wisconsin Maritime Museum in Manitowoc, Wisconsin.